A Love Song for Margaret Atwood’s Poetry Collection You Are Happy

When you are this

cold you can think about

nothing but the cold, the images

hitting into your eyes

like needles, crystals, you are happy.

Margaret Atwood, “You Are Happy”

In the beginning, before I gave myself completely to poetry, I knew that in order to love it I would first need to trust it. Margaret Atwood was one of the few authors I completely trusted, namely for The Edible Woman and Cat’s Eye, books that in retrospect feel as much like my own history as they do novels on a shelf. The best aspect of a formative book is forgetting all about it, and then realizing that you never could forget it, and that is how my relationship with Atwood’s You Are Happy became an enduring one.

This collection was published in 1974, and my copy has a cover with vintage flamboyant orange letters and a vibrant, shaggy sun in the middle. This is Atwood’s sixth volume of poetry, and individual poems appeared in The Atlantic Monthly, Field, The Nation, Poetry, and numerous other magazines. The collection is divided into four discrete sections—You are Happy, Songs of the Transformed, Circe / Mud Poems, and There is Only One of Everything—and the sun makes a return in the penultimate section as design flourish and divider. Weighing in at 96 pages, this book feels sturdy in the hands, and my copy is watermarked from a time I dropped it into the tub.

As contemporary readers, are we prepared for a poetry collection titled simply You Are Happy, with no period at the end or implied question mark, no hint of whether the statement is tinged with irony or delivered with confidence? Returning to this book, I wondered if it would feel dated, like the copy of Our Bodies, Ourselves that for a while served as its shelf-mate before I owned enough poetry books to organize by genre. Like many titles in my collection, You Are Happy was discovered in the joyful abyss of John K. King books in Detroit. I wasn’t its first owner, but I am its most faithful. In the upper right-hand corner of the first page, someone (not me) penciled “4—pm.”

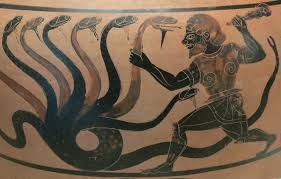

Thankfully, these poems are just as strange and challenging today as they were in 1974. I feel their presence in much of my own current work. Often I attempt the following litmus test with poetry collections that I encounter. Before embarking upon the first poem, I read the table of contents as a poem, and see if it holds a key to understanding the book as a whole. I do this with my undergraduate classes, asking students to read aloud from the list of titles. I am most struck by the titles in Atwood’s Songs of the Transformed section of You Are Happy. A sampling: Pig Song, Bull Song, Rat Song, Crow Song, Song of the Worms, Owl Song…. What I admire about these poems is that they present the song subject first, and then immediately divert the reader elsewhere, often as a vehicle for identifying or reconfiguring the poem’s speaker (or speakers). For example, “Song of the Worms” begins, “We have been underground too long, / we have done our work, / we are many and one, / we remember when we were human.” The reader clings to the initial “we” as an invitation from a collective (worm) presence, only to have this perception challenged by the suggestion that perhaps the speakers were once human and not always part of the worm faction.

Is this one of the many transformations present in the book, located throughout the collection rather than housed solely in one designated section? Is it a statement on our own looming mortality? Perhaps it is just a darkly playful device for making us imagine our everyday concerns in a new light. Later in the book, the poem “First Prayer” uses a similar technique to separate the body from its expected form: “O body, descend / from the wall where I have nailed you / like a flayed skin or a war trophy,” Atwood writes. “Let me inhabit you, have compassion on me / once more, give me this day.” As in all of these poems, Atwood seems undaunted by the aspirations of each piece, and embraces surprise, and at times revulsion, as elements to propel the poem. Looking back, I recognize that I learned this from her, and I am grateful that You Are Happy was one of the earliest poetry books that I encountered.

As a poet, Atwood is utterly unafraid of confronting her audience, which we learn from the first poem of this collection, titled “Newsreel: Man and Firing Squad,” and much of these poems’ success derives from their depiction of the body in unusual forms and unexpected incarnations. The collection’s title poem, You Are Happy, does not address the body directly, but rather presents itself as a meditation within a landscape, making readers vulnerable to the imperative of the speaker, so that the final couplet finds us primed for its statement: “you are happy.”

Questions to consider regarding the book:

For those who are familiar with Atwood from her short fiction and novels, did you see any thematic crossover between the poems in You Are Happy and Atwood’s prose fiction? Do the poems foreshadow any of Atwood’s future interests?

Atwood is known to have a passion for social justice, particularly women’s rights. How would you describe the feminist message apparent in these poems? What other themes are prevalent in the book?

You Are Happy is forty years old. Have its poems stood the test of time, both in terms of craft and content? To this reader’s eye, the use of repetition in poems such as “Owl Song” feels especially contemporary, and the collection’s preoccupations are still quite relevant today.

What do you think of the sequencing of You Are Happy, with its separate, chapbook-like sections? Does the Circe / Mud Poems section function as a long poem? Can you imagine any alternate ways for the collection to be arranged, perhaps intermingling poems from each section?

Try reading the table of contents as a poem. How does it sound, and what does it seem to say? Have you tried this with other books of poems, including your own, if you are a poet?

Do you have a favorite section in the book, or a favorite poem? If assigning a class to do a mimetic exercise in response to Atwood’s poetry, what would the instructions be? What would the students learn from the assignment?