Rika Lesser is a poet and translator of Swedish and German literature. She is the author of four collections of poetry: Etruscan Things , All We Need of Hell, Growing Back: Poems 1972-1992 , and Questions of Love: New & Selected Poems . Her work has been published in Literary Imagination, New Republic, Paris Review, Pleiades, Ploughshares,Poetry, The New Yorker, Threepenny Review among others, and she is the recipient of numerous prizes including the Fulbright Senior Scholar Award, two National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellowships for Translation, Yaddo Fellowship, twice the Translation Prize of the American-Scandinavian Foundation for selections of poetry by Göran Sonnevi and most recently The Greek National Translation Prize (2014) with Cecile Inglessis Margellos for The Brazen Plagiarist: Selected Poems by Kiki Dimoula.

Rika Lesser is a poet and translator of Swedish and German literature. She is the author of four collections of poetry: Etruscan Things , All We Need of Hell, Growing Back: Poems 1972-1992 , and Questions of Love: New & Selected Poems . Her work has been published in Literary Imagination, New Republic, Paris Review, Pleiades, Ploughshares,Poetry, The New Yorker, Threepenny Review among others, and she is the recipient of numerous prizes including the Fulbright Senior Scholar Award, two National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellowships for Translation, Yaddo Fellowship, twice the Translation Prize of the American-Scandinavian Foundation for selections of poetry by Göran Sonnevi and most recently The Greek National Translation Prize (2014) with Cecile Inglessis Margellos for The Brazen Plagiarist: Selected Poems by Kiki Dimoula.

A distinguished poet, critic and translator, Richard Howard’s poetry has received widespread acclaim. His many awards include the Pulitzer Prize, the American Book Award, the Harriet Monroe Memorial Prize, the PEN Translation Medal, the Levinson Prize and the Ordre National du Mérite from the French government. For many years he was the poetry editor of the Paris Review. He won the 1970 Pulitzer Prize in Poetry for his collection Untitled Subjects, and his collection of essays Alone with America: Essays on the Art of Poetry in the United States since 1950 (1969) has been praised as one of the first comprehensive overviews of American poetry from the latter half of the twentieth century. He has authored 17 books of poetry. His latest is A Progressive Education, published by Turtle Point Press, Oct. 2014.

A distinguished poet, critic and translator, Richard Howard’s poetry has received widespread acclaim. His many awards include the Pulitzer Prize, the American Book Award, the Harriet Monroe Memorial Prize, the PEN Translation Medal, the Levinson Prize and the Ordre National du Mérite from the French government. For many years he was the poetry editor of the Paris Review. He won the 1970 Pulitzer Prize in Poetry for his collection Untitled Subjects, and his collection of essays Alone with America: Essays on the Art of Poetry in the United States since 1950 (1969) has been praised as one of the first comprehensive overviews of American poetry from the latter half of the twentieth century. He has authored 17 books of poetry. His latest is A Progressive Education, published by Turtle Point Press, Oct. 2014.

On the Condition of Humans and Other Animals — An Appreciation of Richard Howard

Richard Howard is a man of letters, a master of letters, much celebrated as poet, translator, critic and essayist. Long a Professor of Practice at Columbia’s School of the Arts, he is also the most generous of teachers, writing blurbs, forwards, afterwords, and recommendations for countless students and colleagues. By now he has translated closer to 250 French works, not the 150 or more stated for decades in bio notes. His translations include Charles de Gaulle’s war memoirs, Charles Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal (American Book Award, 1983), Roland Barthes, Simon de Beauvoir, André Breton, Albert Camus, André Gide, Maurice Maeterlinck, Alain Robbe-Grillet, Antoine de St-Exupéry, Stendhal and Jules Verne. His honors and appointments would fill at least a single-spaced page.

My teacher at Yale first in Spring 1972, my advisor during senior year 1973-4, Richard Howard taught me a great deal, if not all I know about how to read and write. My Scholar of the House thesis comprised my earliest attempts to write poems, as well as translations of Rainer Maria Rilke–scarcely the household word he would become–and an assortment of Swedish poets, primarily Tomas Tranströmer and Gunnar Ekelöf. Richard Howard’s 85th birthday falls on Monday, October 13th this year, which for me signifies more than forty years of pleasure knowing him as mentor, colleague, and friend.

In Untitled Subjects (Pulitzer Prize, 1970 he began to perfect the dramatic monologues he is so well-known for. In Two-Part Inventions (1974) he turned monologues into dialogues. Throughout his oeuvre many extended poems are syllabically shaped letters, diary entries, speeches and conversations read, spoken, or overheard by their writers. Some examples: an imaginary meeting between Walt Whitman at home on Mickle Street and Bram Stoker, author of Dracula; seven long letters from a former student addressed to his Professor Santayana. Several members of the James family–William, Henry, William’s daughter Peg, her fiancé Bruce Porter–exchange letters amongst themselves and in one case with Lymon Frank Baum, author of the OZ books. The periods in which all characters live and move are fabricated, cut from whole cloth. Contexts for the meetings of these minds result from Howard’s extended reading into the past, a point made over and over again in the poems themselves.

Wordplay occurs in virtually all of Howard’s poems–not surprising for a translator who began to learn French before the age of three. Puns, inversions, re- or displacements–“let lying dogs sleep,” ”the chair she sat in like a furnished bone,” “It’s abstinence that makes the heart meander”–prove him to be a comedian, also in poems that light the darkness of our shared lives. One of his funniest, “Five Communications” discourses on mistranslations from Human to Dog and vice versa. There are four letters, on the subject of a Japanese product, between Annabelle (Mrs. Thomas) Eden or her husband, and CEO Nakamura, along with an in-house memo from the CEO’s partner, whose gender Mrs. Eden gets wrong. The claim for dE-BARK software is to make voice-recognition of dogs intelligible to their owners. Mrs. Eden takes Mr. Nakamura to task: “What dE-BARK regards, for example, as frustration / or in some diapasons as desire / had much better be rendered as: Oh, There Goes a Cat!” A dog’s notion of appetite, is “more clearly focused by the words:// Drop That, Drop That: I’ll Eat It!“

Howard’s oeuvre is replete with both closeted and open homosexuality. Whether gay happenings occur at elegant parties or in New York City’s meatpacking district his voice encompasses them. “Phallacies (I-IX)” are interspersed among poems less focused on the male member. In the first of these, “Another Translator,” something is pronounced in public that had better been unheard. Mme Charles de Gaulle, by her husband’s side at a press conference, is asked what she regarded “as the chief significance of life.” She responds with three syllables:

“A penis.” And with an interval

of no more than five seconds, a hand

(with perhaps military promptitude) descended

on her shoulder: “I believe the English word you mean,

ma chérie, is pronounced ‘Hap-pi-ness.’”

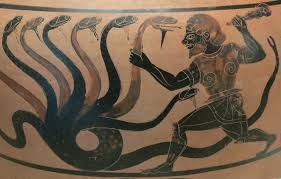

From Untitled Subjects (1969) through A Progressive Education (October 2014) Howard directly pays homage to or writes elegies for writers and artists. These poems often embody or testify to the primacy of the body in and of their works. He is not only knowing but wise. I offer an extract from “The Giant on Giant-Killing; homage to the bronze David of Donatello, 1430,” an ekprhasis in which the artwork itself speaks:

I am from Gath where my name

in Assyrian means destroyer, a household word

by now, and deservedly. Every household needs

a word for destroyer . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

and my name is a good word.

Try the syllables on your own tongue, say Goliath.

It sounds right, doesn’t it–powerful and Philistine

and destructive, somehow. It always sounded like that

to me. Goliath! I shouted, and the sun would break

in pieces on my armor.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The end came as a body.

You see, I am past the end, or I could not know it:

look at my face under his left foot and you will see,

look at my mouth–is that the mouth of a man surprised

by the end of the world? Notice the way my mustache turns

over his triumphant toe

(a kind of caress, and not the only one), notice

my full lips softened into a smile. . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

I am the man Goliath, and my name in Israel

is also a household word,

every household needs the word . . .

but it is a good word, my name; try it on your own

tongue, savor the hard syllables, say Goliath

which in Hebrew means exile.

A Progressive Education came out last week. The cover photograph is of the childhood friend to whom the book is dedicated: For / Anne Loesser Hollander / who, following me / (one year behind) / has shared with me / our Park School lives / ever since. A poem rooted in Cleveland appears in Findings (1972). “From Beyoglu” is a letter to Anne; hearing “Finlandia” on the radio jolts Howard’s memory to recall an episode from The Park School:

. . . Finlandia. Dearest Anne,

do you remember the year we were

Vikings? Monday after Monday, Miss Petersen

started off with The Silver

Songbook, Sibelius, “O land of lakes

and azure streams a-flowing.” . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . children

shrilling Sibelius in a ring,

supposing the black Finns to be their blond Vikings–

we were those children, we sang,

we suffered, we were there. Where were we?

The starting point for Richard Howard’s delight in words, indeed for his erudition, is to be found at that school. Although four of these poems, now revised, first appeared as the sequence “School Days” (Without Saying, 2008), the book just published has eleven more. Most are in the voices of pre-adolescent sixth-graders, children writing to their Park School superiors–the principal, Mrs. Masters and two teachers, Miss Husband and Mr. Lee. The students receive responses from them and an apologetic note from David Hammerstein’s mother, who arrives late for her school visit. This childhood reimagined takes place in the year 2000, during which the children learn about death and life.

A Progressive Education differs from all of Richard Howard’s other volumes of poetry in being the most openly autobiographical. The speakers-letter-writers, six boys and six girls, usually write with one voice–although they have differences, absences, and abstentions. All together they are altogether hilarious. In the conglomerate of roughly ten-year-old pre-adolescents, I cannot help but hear the voice of a boy, one of the precocious boys. It sounds just like its inventor. Both sexes are curious, observant, and vocabulary-loving; they search for their selves and for the social meaning of life. When they have a difficulty, they write to Mrs. Masters, who will answer as the book concludes. Their problems are many and various. Sometimes with one another. Sometimes with the form of their instruction, which delights, disappoints, or scares them.

There have big problems with dinosaurs, evidenced by the letters “Our Spring Trip” and “Back from Our Spring Trip.” In Sandusky, David Stackover bites Arthur Engelhurst for allegedly making their model dinosaur collapse. On their trip to New York’s Museum of Natural History, they learn how to balance the head and tail. Arthur Engelhurst does kill a huge, male, ten-year-old peacock, kicking and stomping on him in The Park School’s parking lot, while attempting to properly kill a vampire. His classmates want him to be expelled. Mrs. Masters does not oblige them. Subsequently, however, they learn that Arthur’s late parents were Hasidic Jews who practiced kapparot, a ritual in which Believers swing live chickens over their heads and then sacrifice them. Not older but wiser, the class changes its mind about punishment. (“Arthur Engelhurst’s Back in School”)

In earlier books Richard Howard wrote amiably about animals, most often companionable dogs. Here he shows the children pondering matters of life and death–“we’ve already figured it out, about death: The Dinosaurs / may be extinct, but / they’re not dead!” In their hands-on Science Class (“A Sixth-Grade Protest”) a pig-farmer lets everyone touch a piglet. When returned to its litter, “the mother pig ate it right there / while she was nursing the rest.” Another visitor brings a python to school, which later inexplicably crushes its owner. In another poem, Dr. Morton–who prefers to be called Mort–induces cancer in mice. Again a mother, the foster mother, devours the aliens along with her own babies. Righteously upset, the whole class protests to Mrs. Masters (“A Proposed Curriculum Change”):

Mort’s lab first spelled out:

in the Animal World–and aren’t we

animals too?–mothers and fathers always

consume their own young, regardless

of shapes or sizes–

pigs in model farms,

Komodo dragons,

and now even mice!

Maybe our own parents will eat us

sooner or later–

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Is all Science a history of death?

Maybe we’ll find out in Seventh Grade that no Fate

is worse than Death after all, and that

Life will be . . . our Fate.

It is in “What the Future Has in Store” that they learn about S.I., “Sexual Intercourse between Men & Women. . . . / . . . the whole Class / finds it hard to believe that grownup people / voluntarily subject themselves to such / senseless behavior.” Some of the girls object that the film they were shown “made the whole thing seem / disagreeable, / to say the least, and / sometimes really disgusting.” Visiting the Cleveland Zoo’s Reptile House, they are taught about the horrific mating rituals and parental deficits of Komodo Dragons. They also learn the meaning of the word parthenogenesis.

In “A Report Followed by a Remonstrance” the ethical pre-teens see an exhibition of 100 Monochromatic artists from around the world, which they don’t much like. Nor they do like the art teacher’s racial slur on their guest student from Pretoria, their one black student. “Mrs. Eynon had taught us / Space and Time, Composition and Color, / but what about Black and White?”

Finally they learn about literature and life and to make distinctions between them. Miss Husband sends them to the stacks of the Park School library, where they first understand that they must “dig awfully deep / for what we didn’t know we were looking for.” In this case (“E Pluribus Unum”) about an author with a double life: dog-hater Charles Dodgson / Lewis Carroll, who populates the Alice books with rabbits, mock turtles, caterpillars, oysters, dormice, and other small creatures:

Maybe that’s the true allure

of libraries–lighting on

a proper author’s scandalous life

right next to the official version.

Out of the mouths of these youngsters come the techniques and pyrotechnics of Richard Howard’s adultstyle. Never before in his poetry has Richard Howard expressed himself, his entire enterprise, so plainly, so forthrightly.

Questions to consider:

- The excerpts I have chosen, as well as the poems in A Progressive Education are in syllabics rather than “received forms.” To what effect is this done?

- How much familiarity do you have with the subjects of Untitled Subjects? Would not knowing “send you to the stacks” or lead you to putting down the book?

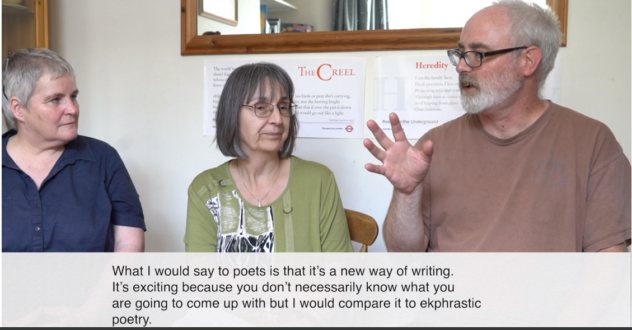

- Howard writes many ekphrastic poem. Do his descriptions of the art works allow you to see them? Would you go to the works or lives of the artists to assist your appreciation?

- How are the poems in A Progressive Education different from the rest of Howard’s poems–stylistically, in other ways?

- Is Howard a tragedian? a comedian? Something else?

View the discussion on YouTube