Scott Wiggerman runs Dos Gatos Press in Austin, TX, with his partner, edits and publishes the annual Texas Poetry Calendar, the Wingbeats Exercises & Practice in Poetry series, as well as other Dos Gatos titles. He leads poetry and writing workshops in Alpine, Texas, and has authored two books of poetry, Vegetables and Other Relationships (2000, Plain View Press), and Presence (2011, Pecan Grove Press).

January 7 marks the 40th anniversary of the death/ suicide of Thomas James at the age of 27. His sole book of poetry, Letters to a Stranger, originally published by Houghton Mifflin, was reissued in 2008 by Graywolf Press. His poetry was influenced Plath, some in direct dialogue with Plath’s Ariel. Of his life in Illinois, little is known. He painted, he wrote plays, he wrote poetry, he collected walking canes, he was gay, he exited life with a bullet in his head.

January 7 marks the 40th anniversary of the death/ suicide of Thomas James at the age of 27. His sole book of poetry, Letters to a Stranger, originally published by Houghton Mifflin, was reissued in 2008 by Graywolf Press. His poetry was influenced Plath, some in direct dialogue with Plath’s Ariel. Of his life in Illinois, little is known. He painted, he wrote plays, he wrote poetry, he collected walking canes, he was gay, he exited life with a bullet in his head.

Scott Wiggerman on Thomas James

I discovered Thomas James in the same way I have learned about many writers’ work, a daily poem delivered to my email box by the Poetry Foundation. I was in the midst of preparing a syllabus for the Alpine Summer Writers’ Retreat a few years back, and as soon as I read “Mummy of a Lady Named Jemutesonekh,” I knew it would make a great addition to the afternoon I was planning on persona poems. Several months later, at the Graywolf Press booth at the annual conference of the Association of Writing and Writing Programs (AWP), I was browsing through books when I came across this same poem in Thomas James’ Letters to a Stranger. I admit that I had not remembered the name Thomas James until I serendipitously found the poem in the collection, which I immediately bought. I was not disappointed; in fact, I read the entire book on the flight back to Austin, and I’m delighted to say that Thomas James and his poems are no longer strangers to me. My wish is that they will become familiar to listeners of Public Poetry’s Ex Libris book club as well. This is a poet who deserves to be read.

In 1973, shortly before his death, Thomas James produced his only book, which contained 41 poems and quickly went out of print. In 2008, Letters to a Stranger was revived by the Graywolf Poetry Re/View Series, which added 13 uncollected poems and a substantial introduction by Lucie Brock-Broido, containing most of what the world knows about the man born Thomas Edward Bojeski (try Googling him and you will see how little information is out there). Letters to a Stranger, then, is James’ complete oeuvre—but what a legacy he has left behind.

In poem after astonishing poem, James presents his “letters” through wild metaphors, graphic imagery, and intense self-reflection, as though he were the heir-apparent to Sylvia Plath, and perhaps he is. His subjects are many of the same she explored in Ariel: loss, stasis, death, resurrection. The titles alone—like “Laceration,” “In Fever,” and “Luncheon with the Hangman”—echo some of Plath’s. Given the subject matter, it’s no wonder that James’ poems are dark, but they also often employ unexpected humor and sensuality in the way Plath’s do. If she is Lady Lazarus, he is Lord Lazarus. It is no surprise that both poets ended their lives way before their time.

What I find startling, however, is the exquisitely wrought language throughout the poems, metaphor after metaphor that is original, provocative, perfect. Some might contend that James overdoes metaphors in his poems, but for me, they make these dark, death-riddled poems come to life. Consider the persona poem, “Old Woman Cleaning Silver,” whose arthritis is described as “the kind of pain that comes / Out of the heavy silvers of the mirror / Or the white fields at the end of December.” Or from “Frog,” another persona poem: “Thin as any witch, / The moon comes up the hill in a stiff hood // Of gold.” Or these final lines of “Dragging the Lake”: “They reel me in, a displaced anchor. / The cygnets scatter. I rise, I nod, / Wrapped in a jacket of dark weed. / I dangle, I am growing pure, / I fester on this wooden prong. / An angry nail is in my tongue.” Or in “Longing for Death”: “It is easy to surrender to the point of a needle: / It is like lying down to love / With the smell of August rubbed into your skin.” I could go on and on with examples. Even the less successful poems in this book have at least several lines like these that make me want to read and reread them for their sheer beauty.

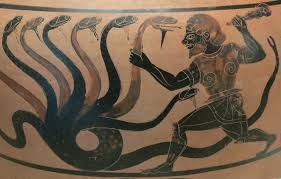

A letter, by its very nature, is written by someone to someone, and part of the joy of the poems is also in working through who is writing these lines to whom. As mentioned, many of the poems in Letters to a Stranger employ narrative personae, often indicated by the titles, as in “The Bellringer,” “The Stableboy,” “Saint Francis among the Hawks,” “Magdalene in the Garden,” or “Mummy of a Lady Named Jesutesonekh.” What’s not as clear is to whom these poems are being addressed. Who is the “stranger” of the book’s title: God? Society? A lover or would-be lover? A seemingly deaf Universe? Or is it simply “you,” the reader of these “letters”? In much the way that the poet Ai uses personae, James employs them to explore the cruelties of living in this world, and, as well, to exorcise his own personal demons. I can’t help but feel that behind each of the personae, there is quite a bit of James himself. Yet most of the poems do not read the way the generation of confessional poets before James do—Lowell, Plath, Sexton, Berryman—perhaps because we know so little of his life and far too much of theirs. (“Reasons,” however, reads very much like a purely confessional poem.)

Death is ever-present. In fact, many of the poems are written from a point near death, from a surreal existence somewhere between life and death, or from the afterlife. In “Room 101,” the persona of a hospital patient slowly transforms to that of a body in a morgue (“I come to trade my flesh for stone.”). Other poems also are told by hospital patients, as in “The Poinsettias,” “In the Emergency Ward,” and “Laceration.” “No Music” is written from inside a casket, whereas “Dragging the Lake” is from beneath the water. “Suicide” is written at the point a bullet nips through the brain, and “Mummy of a Lady Named Jesutesonekh” is told by the dead queen as she’s being embalmed. How interesting that these personae in James’ poems often become more alive as they become more dead. Whether religious in intent or not, resurrection themes abound in this book.

I know that Letters to a Stranger is not the easiest book in the world to find, though I certainly encourage you to make the effort to find it. To make it somewhat easier for our discussion purposes, we will concentrate on five poems mentioned earlier, all of which are easily found at the Poetry Foundation site (yes, the very same site where I discovered Thomas James):

- “Waking Up”

- “Dragging the Lake”

- “Letters to a Stranger”

- “Mummy of a Lady Named Jemutesonekh”

- “Reasons”

While reading these poems—and any others by James—I would like you to focus on the following:

- metaphors and imagery

- themes of death and resurrection

- use of narrative personae and “letters”

Mostly, I want you to learn to appreciate Thomas James in the way Lucie Brock-Broido, Ed Hirsch, Mark Doty, and I do. What lines and metaphors blow you away? How does James keep his death-saturated poems from being completely dark and morbid? How does his use of personae provide both insight and distance? What is it about Thomas James that made him an underground cult figure? Let’s deal with these and other questions you have when we discuss Letters to a Stranger.

View this event on our calendar