LIVE WEBCAST – 7 PM, FEB 23:

Gotomeeting.com #361703309

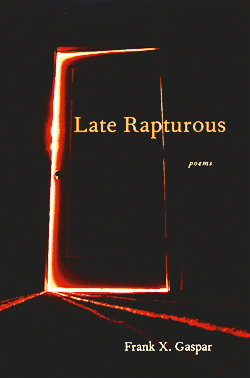

ELLEN BASS discussing Late Rapturous

“I am a great admirer of Frank Gaspar’s poetry.

In his work we are privileged to see intimately into the workings of the poet’s mind. That sense that he opens the window of his mind and lets us look in, is so compelling. Allen Ginsberg said, “Write your mind.” And I think this is what Frank’s poems do.

His poetry inspired me to coin a new poetic term, the long-armed poem, because he reaches out a long arm and scoops so much disparate, seemingly unrelated matter into his poems and yet there’s always a sense of inevitability that these things do belong together—a strong magnetic or gravitational attraction.

His poems combine a keen quality of observation with a deep vulnerability. They plumb despair, but there is always a song of praise in them as well. I asked him about this in an interview that I did with him for American Poetry Review—this joining of despair and praise, and he said:… the despair and praise are not so much a call and a deliberated response, but the rising of two wings that beat together.

It’s this kind of thinking in what, for me, is unforgettable imagery, that makes me return again and again to his poetry.

I hope you enjoy his poems even half as much as I do. And I trust you will feel enriched and inspired by his work.

TWO POEMS BY FRANK X GASPAR FOR DISCUSSION:

June/July—Eleven Black Notebooks at the Desert Queen Motel

Then night again. The dry lightning like artillery over the far reefs

of stone and the thunder-god shearing the air—all the gods in foment

and calamity, but it is not enough. The rumble and rupture, the shattering.

Out there in the wilderness. Isaiah, Ezra, their lamentations, insufficient

in the madness, and me with my tall can of iced beer leaning

at the railing outside my door, like at the taffrail of a ship, but instead

of the big turbines thrumming on blackoil, now only the small throats

of the air conditioners gagging and moaning. The cold aluminum sweats

in my hand, and I’m pleased for this small miracle, water out of the

cracked desert air, but it is not enough. My happiness now, with the

work coming forth in fits and then gouts, is not enough, for it saves

nothing, yet it is a happiness after all, and therefore inexplicable.

The stars crowd one another out of their familiar lines. The arm

of the galaxy, its bright muscle against the belly of the sky. Not enough.

My heart full or empty, not enough. Now, to set something down in

the midst of folly, one true word, one simple cry out of the black arroyos

and dangerous washes, the canyons, the granite redoubts, but the lone sob

of the desert hen is not enough, the television’s mangled voices creeping

through the drywall and stucco are not enough, and I am running out of

time and money, always time and money. And love, I don’t forget love,

but it’s not enough either, it doesn’t save anything, the graves open for all

the beloved to lie down in and all the despised as well, and it is still not enough.

Stepping back into the cramped room I think of that ship again. How a ship will

Fit into the poem at this juncture. Perhaps my own ship from that other time.

One hundred thousand tons of death and empire. Grand under my feet. Rolling

with the long ocean swells. Sky like desert sky, shot with the unutterable trillions.

And the engines banging forward blindly. Into that darkness. Under that blaze.

Late Rapturous

Well, the cold iron wind and the Hudson River from whence it blew,

thirteen degrees on all the instruments and water in my eyes, but

there was a fire someplace, it made my ears burn and sting, and me

buffoonish in my old dirty down parka that I used to sleep in up

in the Sierras with my little tent in the snow—I’d go in on skis by

myself and write haiku in the candlelight because I believed such

things would improve my inner being. But now I was leaning sideways

walking up to 54th street to finally have a look at the de Kooning. I

don’t know what I expected, I don’t know what I was looking for exactly,

except that I’d seen too many prints, too many cramped photos, and

I wanted the full brunt of it, that late rapturous style, that sexual

confrontation that I’d read so much about, the crazy man in the Fourth

Avenue loft before lofts were ever cool, drinking and working, working,

re-working, wrapping paintings in wet newspaper so he could rub things

out the next day and start over and over and over, yes, it was that, I will

admit it, I wanted to stand in the presence of the real thing and feel it—

it’s never the aboutness of anything but the wailing underneath it, and

there was a pain behind my heart and some kind of weird music inside

my ears, so that riding up in the escalators, there came a slow panic at

the swirl of a woman’s long skirt, or a man’s head turned at just the right

moment—no explaining the sources of this, not the smells of body

heat and heavy coats, though I know that every time you run toward

something you love, you run away from it too, you get blinded by the

colors or you miss something important and the moment collapses and

takes whole worlds with it, forever, into some kind of blackness. It was

crowded, that room, but almost everybody was just passing through and

I f found I could walk right up to those canvasses, and I believe I could

have laid hands on them before anyone jumped me, but of course I

just leaned and stared. I don’t know how long. It didn’t matter. What

I needed as to take them with me and slant them against a wall some-

place safe and curl up next to them at night instead of trying to sleep.

It would be the only way. Back outside, I staggered up against the wind

and it blew my tears back, and I finally ducked into a little place selling

hot soup in paper bowls, and everyone was taking something off or putting

something on—they were all talking and moving like they knew absolutely

how to spend every hour of their lives, and not in darkness, either, or in

despair or regret, and when I could see that the winter dusk was running to

silver against the high roofs and towers, I stepped out again into the street,

the shiny cabs cruising and the men and women bundled in long coats and

bright scarves, and the hundreds of windows of the city’s dark pavilions each

showing its square of yellow light, and I walked back into that other kingdom.

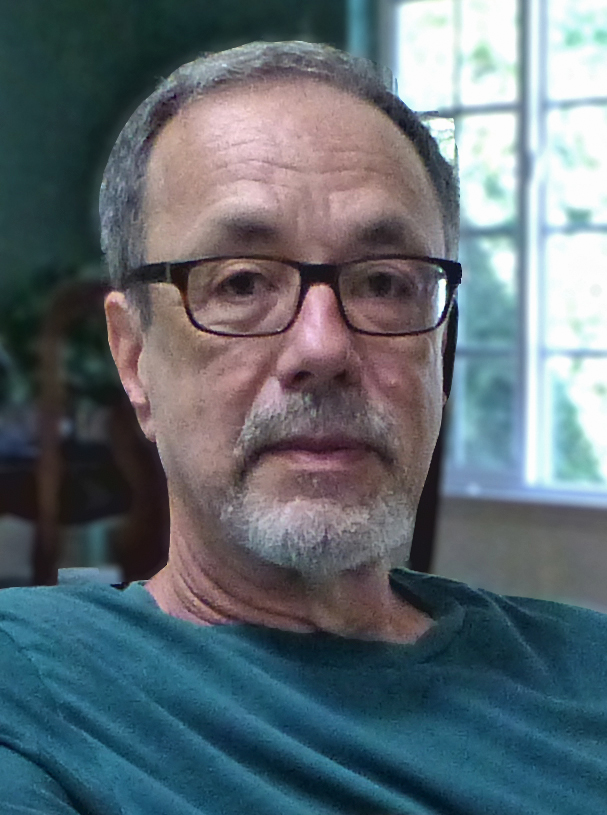

Frank X. Gaspar is the author of five collections of poetry and two novels; his latest collection of poems Late Rapturous, was published by Autumn House in July, 2012. Among his many awards are the Morse, Anhinga, and Brittingham Prizes for poetry, multiple inclusions in Best American Poetry, four Pushcart Prizes, a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in Literature, and a California Arts Council Fellowship in poetry. He was also a John Atherton Fellow at Bread Loaf, and a Walter Dakin Fellow at Sewanee.

Frank X. Gaspar is the author of five collections of poetry and two novels; his latest collection of poems Late Rapturous, was published by Autumn House in July, 2012. Among his many awards are the Morse, Anhinga, and Brittingham Prizes for poetry, multiple inclusions in Best American Poetry, four Pushcart Prizes, a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in Literature, and a California Arts Council Fellowship in poetry. He was also a John Atherton Fellow at Bread Loaf, and a Walter Dakin Fellow at Sewanee.

His work has appeared widely in magazines and literary journals, including The Nation, The Harvard Review, The Hudson Review, The Kenyon Review, The Georgia Review, The American Poetry Review, The Southern Review, Prairie Schooner, The Tampa Review, Miramar, and others. He most recently held the Helio and Amelia Pedrosa/Luso-American Foundation Endowed Chair at the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth. He now teaches in the MFA Writing Program at Pacific University, Oregon. His latest collection of poems, Late Rapturous, was published by Autumn House in July, 2012.

http://www.frankgaspar.com/

“It’s A Bit Mysterious, and I Like That”: An Interview with Frank X. Gaspar

Ellen Bass’s most recent book of poetry, Like a Beggar, was published in April 2014 by Copper Canyon Press. Her previous poetry books include The Human Line (Copper Canyon Press), named a Notable Book by the San Francisco Chronicle, and Mules of Love (BOA Editions), which won the Lambda Literary Award. She co-edited (with Florence Howe) the groundbreaking No More Masks! An Anthology of Poems by Women (Doubleday).

Ellen Bass’s most recent book of poetry, Like a Beggar, was published in April 2014 by Copper Canyon Press. Her previous poetry books include The Human Line (Copper Canyon Press), named a Notable Book by the San Francisco Chronicle, and Mules of Love (BOA Editions), which won the Lambda Literary Award. She co-edited (with Florence Howe) the groundbreaking No More Masks! An Anthology of Poems by Women (Doubleday).

Her poems have appeared in hundreds of journals and anthologies, including The New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine, The Atlantic, The American Poetry Review, The New Republic, The Kenyon Review, Ploughshares, and The Sun. She was awarded a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Elliston Book Award for Poetry from the University of Cincinnati, Nimrod/Hardman’s Pablo Neruda Prize, The Missouri Review’s Larry Levis Award, the Greensboro Poetry Prize, the New Letters Poetry Prize, the Chautauqua Poetry Prize, a Fellowship from the California Arts Council, and two Pushcart Prizes.

http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/ellen-bass