Writing Landscapes, Presences and Absences: A Conversation with John Pluecker

John Pluecker is a writer, interpreter, translator and co-founder of the language justice and literary experimentation collaborative Antena. Publications in 2016 include his first full-length poetry collection, “Ford Over” from Noemi Press, and a translation of Sara Uribe’s “Antígona González” from Les Figues Press. For more information about his writing, activism and upcoming readings, visit http://johnpluecker.blogspot.com/

JP was a Public Poetry reader in 2012

JOELLE JAMESON: How would you describe the personality of your poetry, in relation to your own personality?

JOHN PLUECKER: It’s definitely a lot easier to talk about the personality of my poetry than my own personality! Though talking about the personality of my poems is still hard, because there are so many different and multiple personalities, moods, affect-scapes. Each poem is its own little world. And each reader will have their own particular experience of each poem.

A writer who I really respect once said, “If you know exactly what the writing is doing, then your reader will feel that immediately as well.” I want there to be some mystery to the work, and questions—because I don’t live in a world where I have the answers, and I don’t think my poetry has the answers either.

From your point of view, what is the relationship between the poet and the reader or the listener? What should the reader or listener bring to the work?

John: There’s a million different readers and there’s a million different ways that people will come at a text and poetry. I go back to a Gertrude Stein quote which I may or may not be quoting correctly at this late stage: “If you enjoy a thing, you understand it.” So if you like a poem, or if there’s something in the text or performance that you’re gives you pleasure, then that joy can be an access point into the poem.

Your book, “Ford Over,” dives into the experiences of explorers in what is now the state of Texas. Where did the book start for you?

The book turns back to the foundational time of European colonialism in what we now call Texas: the Spanish and Mexican periods. As I read through the journals and diaries by the colonial agents of those times, it became clear that these men took certain things for granted—for example, that the reader knew what it was like to cross a river in the 18th and 19th century. They used the crossing of the rivers and creeks to mark time and space—for example, the diarist might write, “Today, we crossed three creeks and one river and came to the banks of another river.” Fording a body of water was a unit of measurement of space traversed.

But they never write about how their own bodies crossed the water or what that process was like. Many of these men (and they were all men) would drown in the rivers as they were crossing, and I became more and more obsessed with their drownings—the drownings of these European colonizers as they crossed through the waterways that crisscrossed the land. I was interested in their failure or how drowning becomes a kind of success. I thought and wrote into how these European languages that we use today—English and Spanish—were first applied onto the landscape, and how these European languages were used to delimit space and to write about rock and plant, geology and landscape. If we are ever to have any possibility of decolonizing this land, it seems we have to find ways to un-make or un-settle these European languages we use on a daily basis.

How long, roughly, were you working on the book?

I started doing the first experiments and the work with the diaries of the colonial agents in 2009, so that’s seven years to publication. But I had the same obsessions before 2009, it just took me a long time to figure out how to bring all these obsessions to the page.

Obsessions with Texas history?

Obsessions with history and colonial processes, de-colonial processes, anti-colonial struggles, writing as anti-colonial, and a really deep interest in what we now call Texas. My primarily German Texas family has been here in these lands for seven generations, first arriving to Mexico then living in the nation of Texas and then the state and then the Confederacy and then the state again; I think there is a spiritual and millenary aspect to this attempt to un-make whiteness and European-ness, to un-settle the settlements.

Can you talk a little more about writing as an anti-colonial act—particularly in terms of “language justice” and what it means to be a “social justice interpreter”?

Before I found routes into writing and art, I worked as a community organizer, moving in social justice circles. That hasn’t ended, and interpreting and translating are two ways I support people and organizations who are doing grassroots political work. I believe that interpreting and translating isn’t just a service—it’s part of a wider framework around language justice, as you said, which ties into other forms of justice, like racial justice and economic justice.

One thing that language justice envisions is a world and a country in which English is not the unquestioned dominant language. So language justice provides strategies for building a multilingual world in which many languages exist and continue to exist over time. It asks: how can we change school systems and governmental systems to make space for people to speak the language in which they feel most comfortable or to speak multiple languages? That only makes sense within the context of a wider practice that’s anti-racist and anti-colonial—a practice that’s trying to take apart all of these legacies of colonization and conquest within which we live and move.

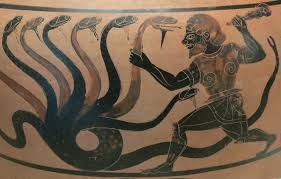

Speaking of translation—tell me about your recent translation of “Antígona González” by Sara Uribe.

Sara Uribe is a writer from Tamaulipas in Northern Mexico, which is the state that borders Texas on the Gulf Coast, just five hours south of Houston. Uribe draws from many different Latin American feminists who used the Antigone myth in situations of war or dictatorship to talk about how women in these societies formulate a cry for justice. In the book, Antígona is searching for the body of her lost brother. It is a hybrid text that’s somewhere between poetry and a dramatic monologue—it was originally written for an actress in Tampico, Tamaulipas to perform.

The story addresses the tens of thousands of people in Mexico who have been killed or disappeared in the last five to ten years. I think it’s critical to hear from Uribe and other Northern Mexican writers on this issue. There’s too little talk in the U.S. about what’s happening in Mexico, and when that conversation does happen, it’s normally from a U.S.-based pundit on the right or the left, not from people who are living through the situation. That’s one really important role I think translation can play—to bring voices into English and into the U.S. which otherwise wouldn’t be heard.

This question is from a Public Poetry audience member: Why is it important that poetry be accessible to all communities, and how can we make poetry more accessible here in Houston?

Poetry can break down mental walls. Poetry can do things. But only if people have access to it (and if they want to engage with it). I get inspiration from poetry festivals like O Miami which are dedicated to getting every single person in Miami-Dade County to encounter a poem during the month of April. They come up with all kinds of radical means to do that: sky-writing poems, urinal poems, poems in donuts, a million wacky and wonderful ideas.

What are you reading now?

A couple of gorgeous books from a San Francisco Bay Area small press that is doing soul-crushingly beautiful work: Timeless Infinite Light: Black Lavender Milk by Angel Dominguez and The Romance of Siam by Jai Arun Ravine.

Is there any kind of writing activity or exercise you can recommend for other writers?

I can recommend a whole pamphlet! Antena released How to Write (More) in 2014, and it’s available as a free PDF on our website. It’s a series of great writing exercises.

Thanks for talking with me today, John. Anything else you want to get off your chest?

My chest is… bare. [Laughs]